The Howard Family |

|||

This memoir was written by

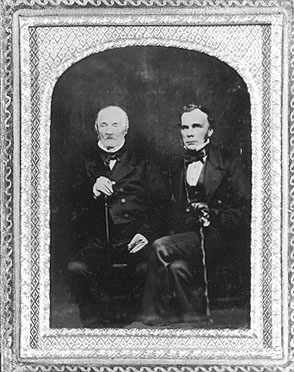

This is a collodion positive photograph on glass dating from around 1850 of Luke Howard and his son John Eliot Howard. The original is now on show at the National Portrait Gallery in the Victorian Rooms (Science Section)

|

JOHN ELIOT and MARIA HOWARD "Children's children are the crown of old men; and the glory of children are their fathers." Maria Howard placed this quotation from the Book of Proverbs on the title page of 'Memorials of John Eliot Howard' which she had printed after her husband's death in 1883.

John Eliot was born at Plaistow in Essex in 1807, and was educated at home except for two years at Josiah Forster's School. In 1823, he was apprenticed to his father at Stratford, and studied practical chemistry. He was made a partner in the firm in 1828, riding daily from the Eliot home in Bartholomew Close until he moved into his aunt Elizabeth Howard's house in Bruce Grove, Tottenham. (See map) Although he had no higher education as we know it, John Eliot became a well educated man. Besides his studies in chemistry and botany, he spoke French and some German. He had learnt Latin and could use Greek quotations to prove a point. In later life he began to study Hebrew because of his deep interest in the Christian faith. His life's work lay in the field of quinine. He was only 20 when his Day Book for 1827 first mentions sulphate of quinine as occupying his attention. Later he was interested in boracic acid, but it was for his study of Peruvian bark and its derivative quinine that he was honoured and acclaimed. His greatest achievement as a pharmaceutical chemist lay in the development of quinine in the treatment of malaria and other fevers. He made a lifelong study of cinchona barks and their chemical constituents from which quinine is extracted. He became one of the world's leading quinologists and carried on an international correspondence. It was for this work that he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1874. The citation for his election states that "the name of Mr Howard is inseparably connected with his lifelong investigation respecting the identification and chemistry of the cinchona". In the 1850s he obtained seeds and specimens of cinchona from South America, and managed to purchase the collection of barks assembled by Professor Pavon of Madrid after Pavon's death. When he finally received this collection, he wrote in a letter to a colleague "It is a great pleasure coming up with the game after such an intellectual chase. Still, there are higher pursuits and nobler joys for the Christian". He cultivated many of the seeds in his greenhouse at Lords Meade and in 1857 was elected a Fellow of the Linnaean Society. A botanist friend suggested to him that "the use of the Herbarium and Library will, I think, frequently prove of service". (These were situated in Burlington House, Piccadilly). In 1862, he published at his own expense the 'Nueva Quinologia', a careful study of a large collection of microscopical mountings of barks. This was in six parts with some thirty coloured plates. (A copy can be seen in the Lindley Library of the Royal Horticultural Society, 80 Vincent Sq, London, and also at the Kew Herbarium Library). John Eliot's second great work, 'The Quinology of the East Indian Plantations', published in 1869, resulted from his examination of the bark of all the forms of cinchona introduced into India from the Andes at that time, identifying the species giving the best yield of quinine. The importance of these two publications and John Eliot's contribution to the development of quinine is widely acknowledged. |

||

|

|

Turning to their family life, John Eliot married Maria, daughter of William Dillworth Crewdson of Kendal in September 1830. He was 22. She was 23. The Crewdsons were a staunch Quaker family already connected with the Howards by marriage as were so many other Quaker families such as Fox, Lloyd, Braithwaite and Wilson. Coming of similar Quaker stock Maria matched her husband in piety, energy and determination. They moved into a substantial house in Tottenham called Lord's Meade after the land on which it was built, oppposite Bruce Castle, the Elizabethan Mansion formerly the Manor House for that area. (This same name was later used for a Howard property at Ashmore in Dorset and other members of the family have since used it!) They lived there for the rest of their lives, raising a large family of four sons and five daughters, born between 1831 and 1848, whose names, dates and marriages are set out in the family tree. Further information about the Quakers in Tottenham can be found here. In 1835 Maria's uncle, Isaac Crewdson, wrote the book "A Beacon to the Society of Friends", which played a key role in the controversy over whether spiritual guidance should be determined by "the Inner Light" or by biblical truths (see paper 5). As a result of this controversy, many Friends left the society in the 1830s. Maria records that her husband helped her uncle with the book. She says "We were Friends and had no thought of anything but remaining Friends". But in 1833, he took "what was then a very bold step, beginning Family Prayers on Sunday Evenings". Throughout 1834, he became very much exercised about Baptism, and in 1836 he first saw the Administration of the Lord's Supper in Glasgow on his way to a meeting of the British Association in Edinburgh, which he attended with his father Luke and his cousin Dr. Hodgkin. In July John Eliot and Maria received Baptism in the Baptist chapel. "On the 6th October 1836, we resigned our connection with the Society of Friends and a few days afterward we renounced Quaker garb". Maria records in her memoir that this was "a step far more painful and formidable that can at this distance of time be understood". In December "we partook of the Lord's Supper at the Baptist chapel where we had been baptised and though not becoming members of the church, we happily worshipped with them". The following year they opened a room for worship at Wood Green and John Eliot began to preach there, being a loyal attender at the twice weekly meetings of the Brethren. Throughout his life he was deeply religious, and his letters to his wife and family are full of gratitude to the Lord for blessing received and for the assurance of grace and for the opportunities they found to bring others to the Lord. He took a small room in Tottenham for worship and the breaking of bread, and when this became too small, he and his brother Robert jointly purchased a plot of land on which the Brook Street Chapel was built. This was opened in 1839, and by 1842 already had eighty eight "members in Communion". A century and a half later it is still the Tottenham headquarters of the Brethren. It was a time of religious controversy both between the Oxford Movement and the Evangelicals within the Church of England, and also within the Society of Friends and the Brethren. Later there was to be the great debate about the historical truth of the Bible, sparked off by Darwin's publication of "The Origin of Species". In 1843, John Eliot wrote "I think controversy good, for even Christians are often so idle and indifferent to truth that they will learn no other way". In 1864, he wrote to his daughter Mariabella that he had been "reading Floren's reply to Darwin which is entirely to my mind in the lucid admirable manner in which he exposes the personification of Nature. ... It is curious to find the French Academics coming forward to maintain the existence of God and quoting Voltaire to this end against our English philosophy". He describes himself in a letter as "naturally and by education something of a mystic and taught to seek God as the existing one if ... I might feel after Him and find Him. In this connection I specially prize the Gospel and Epistles of John, whose special calling was to set right the oriental tendency of thought (prone to Gnosticism) by testifying to that which was from the beginning, which we have heard and have seen with our own eyes and have handled from the beginning" (1 John 1). He wrote a study of the Epistle to the Hebrews, and in 1858 he wrote that he had been reading a book about the Chinese Empire and another about ancient India and had gone deeply into Buddhism and Indian Philosophy, which he described as "the Quakerism of the East, similar to the thought and feelings of my natal religion in a degree which few are prepared to apprehend". His practice of his faith was indefatigable, but to modern eyes, perhaps a little excessive. His letters are full of expressions of his belief in a merciful God. He writes to Maria in 1861 "How rich I feel in you, dearest, and how rich we both are in our children. Surely it is a recompense for many anxious hours to see such a family as ours growing up to take their place in society. My alone trust is in the mercy of God from first to last". Their children all married partners of like stock, with strong Quaker principles as the roots of their upbringing. But he regrets that Eleanor who could write well for children should "write airy nothings and romances. She should try to tune Children's hearts to David's Harp or Isaiah's Lyre". His wife Maria was obviously a great helpmeet to him and a very intelligent and educated person herself. In 1874 she remarks on "the pleasure of some quiet evenings at home with much enjoyment in reading together part of Prideaux' Connection. We got through a great deal of reading and I so greatly enjoyed sharing the work with him and having the advantage of his acute and discriminating mind". John Eliot wrote a number of religious pamphlets including "Seven

Lectures on Scripture and Science" published in 1865. He also wrote poetry including

a translation of Goethe's two poems on his father's Classification of Clouds. Goethe had

been an admirer and correspondent of Luke. |

||

|

Their children seem to have been equally well educated. One of their sons, Dillworth, joined his father in the family firm, which became Howards and Sons in 1858. His daughters were also very able. Mariabella accompanied him to Berlin to an Evangelical Conference, which was followed by visits to business contacts in Weimar and Jena, when she acted as his interpreter. Mariabella records "I remember well dearest father's vivid interest in everything and the pain he took to learn and understand. In these respects he was a splendid traveller". A letter records that Alice translated a paper from German for him. The family were great travellers. Maria's memoir records constant visits to relations, to Luke at Ackworth near Doncaster, to her family home at Kendal, and to the married daughters at Wellington, Somerset, Birmingham, and Areley Kings, Stourport. They also visited seaside resorts for their health, Buxton Spa for a cure, and Torquay where John Eliot became very interested in Gough's Caves, about which he wrote two pamphlets. He also travelled on business to exhibitions and to Paris, Berlin and Switzerland where they had a very enjoyable holiday. They were often away from home for several months together. Although they lost none of their own children while young, they were deeply moved by the death of their first grandchild and the early deaths of several others. They especially mourned the death of their own son John Eliot at the age of 28 after much illness. |

||

|

Below is the original memorial which members of the family renovated in 2003 |

John Eliot died on 22 November 1883 at the age of 75 after a brief illness. After his death Maria compiled "Memorials of John Eliot Howard" which she had printed and distributed privately in 1885. She outlived him by eight years and died on 23 March 1892 aged 85. They are both buried in Tottenham Cemetery. It was after Maria's death that their grand-daughter May Fox started the Lords Meade Budget to keep the extended family in touch with each other. In 1883 during the last months of his life, John Eliot Howard was presented with the Hanbury Medal of the Pharmaceutical Society for his life's work on quinine. Afterwards he recorded in a letter to Maria "It is so pleasant to me that my dear children and grand children should be able to point to such a solid recognition of my labours. I had the opportunity in my little speech to say that I esteemed my highest honour to be a Christian - a distinction we all share. Gloria et Laus Deo". |